Many years ago, I had a dream that I was playing soccer in my high school’s stadium. A parent on the sidelines was being extremely belligerent, and interfering with our ability to continue the game. And so, somehow, with the logic of dreams, I shot her. I don’t remember any direct argument between us that lead up to it, just the moment and (more especially) the terrible moments that unfolded after.

The stadium was still lit for game play, but empty save me (still wearing cleats and shinguards) and another mother, telling me that from now on, no one would love me.

It has been days now since the shooting in Connecticut, but the event still weighs heavily on my mind. I keep thinking about the children, six and seven, the teachers and administrators who died trying to protect them.

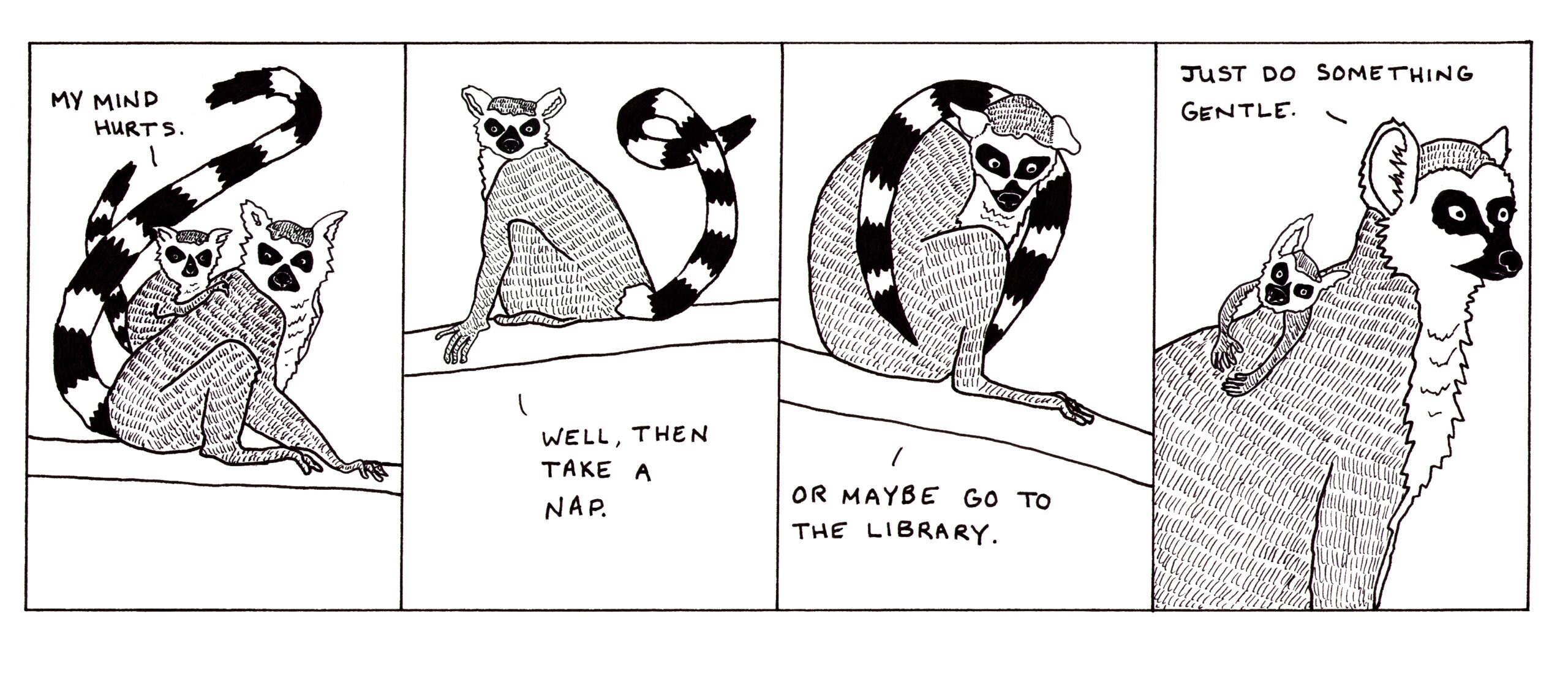

And I keep thinking about my dream, the ease with which – inside that dream – I crossed the boundary from a normal life to an unforgivable one. In reality I cannot even fathom taking part in that kind of reprehensible, terrifying, bloodshed. But it does make me wonder what our role is, as observers and victims of this kind of crime – what sort of compassion is needed to temper the anger, the fear, the devastation?

By chance I was listening to an old This American Life episode the other day, one from the show’s first year of production, entitled “Anger and Forgiveness.” The first segment focuses on the aftermath of another terrible crime, one in which a mother drowned her two young children. TAL taped a conversation between two men, one asking for compassion (in addition, it should be said, to punishment) for the mother, and one arguing that compassion for criminals of this kind is weak and inappropriate.

The writer Jack Hitt, who was arguing for the side of forgiveness, made the point that the mother had herself lived a terrible life in which her father abused her repeatedly. His interlocutor asked: so do we also have to show compassion to her father then? Where does all this compassion end?

Nowhere. That’s the answer. Compassion has no necessary end.

I don’t know what this means in practical terms except that focusing on love and care for one another is more important now than boiling our rage until it burns us. I know that today is my father-in-law’s birthday, and that since his death the love in our family – for Doug, for each other – has been at least as important as the pain of his loss.

I know that it is also my sister’s birthday, and my sister-in-law’s, and another good friend of mine. And that I am in Seattle, where it has snowed – a rare treat, to see such a dusting on our so many evergreens. I know that the world is frightening to me, and sad, but also beautiful, endlessly, gorgeous.