We lost our sweet Paul on Friday. We knew it was coming. He was almost eighteen years old—by the birthday we celebrated for him, he would have reached eighteen on Christmas, but since that date was a wishy-washy estimate given to us by the shelter we adopted him from, we decided to appoint him the age of majority. My heart is shattered. I am so grateful to have loved him for so long, and it is unfathomable to me that I will never see him again in this life, except perhaps in dreams.

We adopted Paul during my first year of grad school, six months after we got married. Just before Christmas, I told Dave I was going to go to the shelter “just to look” at dogs. Dave knew better and insisted on coming: I’d had dog fever for months, the way people get baby fever. Every dog on the street turned my head, and I had perused the photos and bios of every dog on the shelter website many times. Based on his picture, I thought Paul would be too big (he always seemed bigger or smaller than he was in photos: his actual size was Perfect), but when we met him we immediately fell in love, despite the manipulative way the shelter had named him “Prancer” and given him the aforementioned Christmas birthday to persuade December adoptions. The problem was, we were about to leave town for two weeks, first to Utah to spend Christmas with Dave’s family, and then, with a one day interval at home, a week in Seattle to see my family for New Year’s. It seemed insane to adopt a dog and immediately put him in a kennel for two weeks, so we decided on an equally deranged compromise: we would go to Utah, and if this Prancer fellow was still at the shelter when we got home, we’d adopt him and put him in a kennel for one week.

By the time we were driving home, given the closure of the shelter on Christmas Eve and Day, we were pretty sure we were going to get him, and spent the entire twelve-hour drive home thinking up potential names. Schnebly was one, because we passed Schnebly Hill in Sedona, and it sounded funny; the one we liked a lot was Duck, though when I called the kennel to make an appointment we still hadn’t decided, and I spat out “Um, Duck!” and probably sounded insane—you don’t know the name of your own dog? But we didn’t, yet. Even after we decided that Paul was the correct name, his true name, the kennel always referred to him as Duck, with great affection.

A non-comprehensive list of names and nicknames: Paul, Paul the Apostle, Grumble Puppy, Pablo, Pablito, Pavel, Doctor Ears, Paul the Hero, Smooshy, Face, Smooshy Face, Goomba, Baby, Buddy, Bear, Pumpkin Pie, Paul Howlywood (when I was baking), The Puppy of the World.

Speaking of Doctor Ears, Paul’s ears were extremely expressive. The first time I knew we were really bonded was when he would let me put the tips of his soft ears in my mouth and gently nibble them with my lips. When we came home and he was happy to see us he curled into a circle and made Robin Hood Ears, i.e. triangles angled back like Robin Hood’s hat. He often had one ear up and one back or to the side so he could listen in surround sound. He liked eating bees. That’s not related to his ears, I just thought of it, because I imagined him listening for bees in our backyard.

Looking at old photos of Paul, it’s clear to me how much he had aged in the past few years, based on the things he couldn’t or didn’t do anymore. His tail was rarely, if ever, curled up, and neither Dave nor I can remember the last time he sat on purpose (though he often did by accident trying to turn, or get something to eat, or avoid being brushed, because his back legs got very weak and he couldn’t get purchase on the slippery floors. We bought two rugs for him, to help him stand up, and they did help, but it was still a struggle). I found a video of him running back and forth in the yard between two holes he was digging—he loved this! He would sprint back and forth and dig madly in each hole, in a show of total joy and vigor. Then he’d crawl behind the shed, get stuck, get covered in spiderwebs, worry me that he was going to scratch his corneas, which he did once somehow, and which took weeks and many hundreds of dollars to fix. I didn’t want him to go through that again. But he loved crawling behind things, including the futon in what is now Harvey’s bedroom but used to be Dave’s office. There was nowhere to go, behind that futon, no space to turn around, and we’d have to pull him out by his tail; I still wonder if there was a door to Narnia on the other side that only he could see.

Paul was not a fetching dog, but he did like to play “fetch” with his toys sometimes, a game wherein I would throw the toy and then follow him to it, watch him pick it up and shake it violently, and then take it out of his mouth and throw it again. His favorite toys were always his squirrel babies: we still have two of these, one eviscerated, one whole. He carried his squirrel baby around in his mouth for comfort, whining sometimes, and he would lick and groom it and gently bite the eat with little snick snick teeth—just the front teeth—until some Rubicon was crossed and then he’d pull out all its fluff. He liked to hear them squeak. He would let me balance all his toys on his back for pictures, and he would occasionally place all his toys in a pile on the floor just so he knew where they were. He had a strong sense of what was his—he only picked up a shoe one time, and it was a shearling slipper, so of course it basically looked like a toy. He did consider most stuffies to belong to him, including one purloined Bucky Badger, which he undressed and the pulled the eyes out of—lovingly, of course. Once Harvey was born though, Paul never mistook Harvey’s toys for his, although Harvey did not have the same discernment and would occasionally gum a squirrel baby.

I was worried about how Paul would do with Harvey, because in his youth he never really understood children; he seemed to view them as a separate and fairly alien species, which is fair enough. But he knew Harvey from the beginning, immediately recognized him as one of us. Not to say he was cuddly with him exactly, but he liked to be near him, and bore with it when Harvey touched him with, it must be said, not always the softest of hands. When Harvey was a newborn screaming every time he had his diaper changed, Paul would wind between our legs for moral support. I genuinely believed, throughout my pregnancy, that I would give birth to Paul—not that we would receive a second Paul-like puppy, but that Paul would be born anew and we would be together again and would go on as we always had, except that I would be his biological mother.

He only once jumped on the bed, and—given that we’d just come home from a trip—I’m convinced it’s because other dogs at the kennel told him they slept on the bed, and he should try it. We moved him off and he never made another attempt, but if he had I would have caved immediately. However, his hair was absolutely everywhere already, so it’s probably for the best. We will be finding Paul’s hair on our possessions for possibly the rest of our lives, and I find this comforting. His preferred way of being cuddled was to be lying on the floor and have one of us lie beside him or on top of him, though he would occasionally bear with it if I picked him up and held him in my lap.

Now when I walk outside I find myself looking at the places where he liked to stop and sniff and pee, wondering what has been going on since he was there, continuing our shared practice of observing that ever-shrinking orbit around our house. Someone has to go on paying attention.

Paul was very sick near the end. He walked incredibly slowly, which drew endless commentary from the neighbors. When I was pregnant and also slow, I didn’t really notice the difference, but people started asking me how old he was and commenting (with insane bad grace, in my opinion) that their dogs had died at similar ages. Later, the tone of the comments changed to wonder and ecstasy that he was still going—“Still trucking!” they’d say—which was almost more painful, because I knew what they did not about the minutiae of his days. He had arthritis and lost a lot of muscle in his back legs; he was increasingly blind and deaf, navigating our home and yard mostly by memory (as we discovered when we took him to an AirBnB last Christmas and saw how completely unaware he was of his surroundings); he was on a lot of pain medications. But worse that all that was the advancing dementia, which left him deeply anxious and confused. In his youth we said he had “night madness,” which meant he got all kooky and playful exactly when we wanted to be watching tv or reading a book; he liked to sit directly behind Dave’s chair during dinner, risking being stepped on. More recently his night madness was confusion; he appeared lost in a dark mire, would get locked in the bathroom, had no turning radius and had to make wide circles, and would periodically run into the walls. We woke up two or three times a night to reassure him and move him back to bed, or else help him up so he could do a lap down the hall and back and hopefully assuage some anxiety. I didn’t want that life for him, but at the same time he still loved taking walks, loved hugs, loved treats, loved eating a little bowlful of pumpkin puree in the mornings, loved licking Eucerin lotion off my legs (non-toxic, I guess, since he did it for a decade), loved taking long naps with his head pressed against a wall/corner/piece of furniture in a way that looked uncomfortable but was, I suppose, very comfortable indeed. So how could I know, I wondered. I did not know how to know.

Earlier in his life people would stop their cars while we were walking just to tell me how beautiful he was, or to ask his breed. Once, outside the Arizona Inn, a man in a car stopped and asked if he could buy Paul; I said that he was not for sale. Another time, outside the Inn, I’m pretty sure that Joy Williams smiled at him. Another time, again while I was pregnant, we got caught in a torrential downpour—water pooling around our feet, wind blowing sheets of rain into our faces, sudden chill—and the concierge let us take shelter in the lobby, even though I’m pretty sure they don’t allow dogs, and they made a big fuss not over me but over the puppy. Everyone who ever met Paul loved him. Younger dogs would see him coming from a block away and drop submissively to their bellies. We think he had a dominant aura, or an occasional fuck-you vibe that was somehow not apprehensible to humans, because on perfectly calm walks other dogs would jump him—one jumped out the window of a car, one knocked a fence, one broke a window of his house trying to reach us. But he was never hurt, so I assume they were just so many young kings, wrestling for the invisible throne.

Another game Paul liked to play was to try and pick up a softball in his mouth. He could not do it, or at least not easily. He found the physics of the ball baffling from every angle. How can it roll! On its own! And it can bounce! What is this witchcraft!

He and I taught each other to burp for emphasis. He would make this gurgling, burping sound if I was taking too long getting him his treat or getting ready for a walk, and one day he was taking too long doing something so I burped instead, and by god it worked: we learned to communicate with one another. We had a language. We took each other as we were, and grew together. He liked to sit just out of reach and give you a come-hither look over his shoulder so you would stretch and strain to pet him. Sometimes I dragged him closer by the tail and he let me. He was less cuddly than me but we found a middle ground, and oh, we loved each other. We knew each other. I never slept in my house without Paul. I wrote all my books in Paul’s company. I spent more time with Paul in the past fourteen years than with almost any human being. Our vet, who loved Paul and called him “the complete package” on more than one occasion, said that there were only a few people in her life she’d known as long as we knew Paul.

When I was a little girl, I wanted a dog just like Paul. A Samoyed, or a mix, which Paul was—Samoyed and Chow Chow. A white fluffy angel with little soft biscuit spots. I can’t believe how lucky I was, I can’t believe I got exactly what I wanted, and that he was even more perfect than I could have known. I can’t believe I got to spend so much time with him, my inspiration and my muse.

There was a store we’d walk into in Tempe, where the guy behind the counter would beam and say, “Cinnamon Chow! Cinnamon Chow!” with such sincere delight that I still hear it in my head all the time.

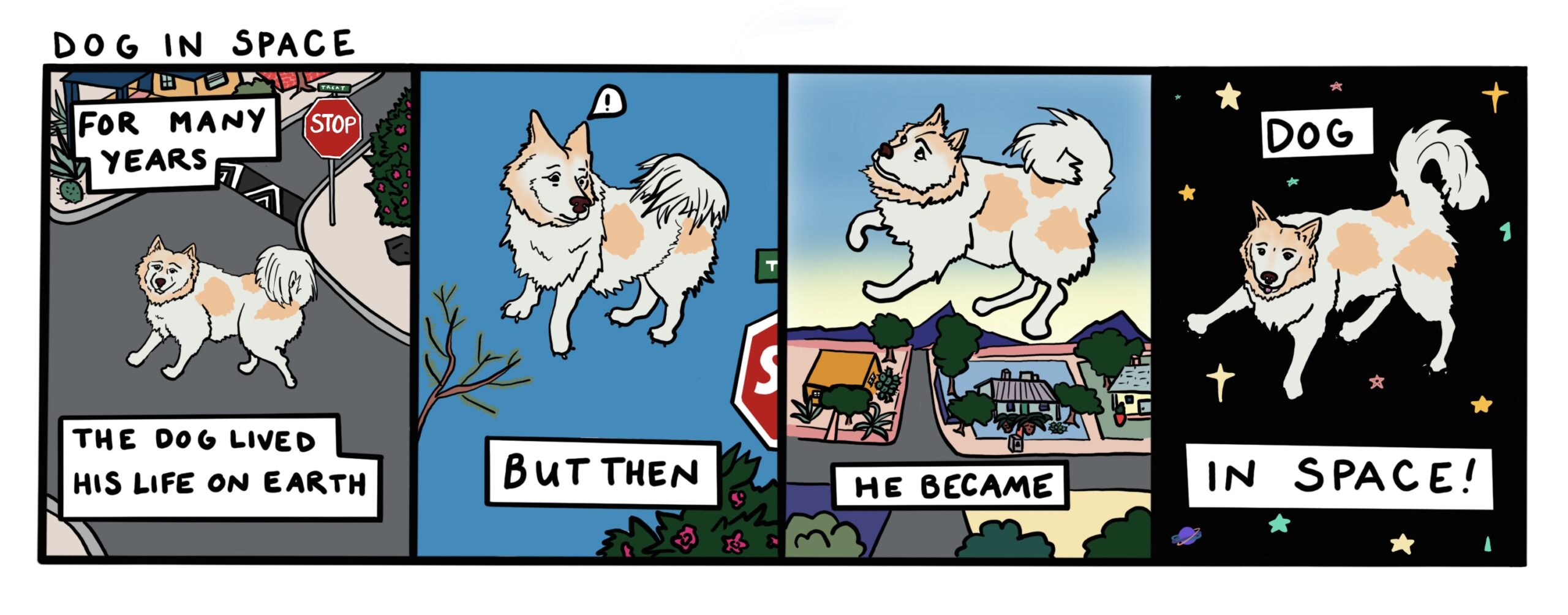

The other day I was talking with a friend about art: I said that making art happens when thought and action are identical. You can articulate what it means to make art outside the act, you can describe it, but you can’t do it, except by doing it. Death is like that. I don’t fear my own death—I don’t court it, I love my life, but I don’t fear it—because at that hopefully distant time I will be the one crossing a boundary and going to someplace new. I will be reborn. I will be with Paul! But watching Paul do it and knowing it could not be undone, that I could not follow and make sure he was ok, I could only watch him on his journey and ease it as best I could, that was hard. It’s hard to be the one left. I walk around our house now and there is a layer at Paul height that feels empty. Up here at human level it’s the same, but there in the middle, something’s missing.

I will miss him for the rest of my life. It hurts. It burns. The last full day of his life was like the dark inverse of the day before Harvey was born, waiting and knowing that everything was about to change, though this time we did not want or choose it. But that’s life, isn’t it? Birth and death are always taking turns, in one big zipper merge with the universe.

I always said that Paul would never die, he would Annunciate corporeally to Heaven like the Virgin Mary. And as far as I can tell, he did. He was so peaceful. He was so at ease. He still seemed to be breathing. His ears were still flexible and oh so soft, that hair behind them where I would scrunch my fingers when he burst into the bathroom like the Kool-Aid Man and head-butt my knees while I was peeing. I resisted calling him my baby for a long time, because he was my best friend, really, but he was also my baby.

This is not everything. There are things I am forgetting to remember, because they seem so obvious as to not need stating. They are supposed to be present all around me. The clicking of his toenails on the floorboards. His soul-shaking sweetness. The way he sounded drinking huge amounts of water. The way he used to only eat when we were with him, which we called “celebr-eating.” The boeuf boeuf of his sleep barks, caught in his cheeks, when he chased dream cats. Back-scratching his feet in the dirt. Scratching his back on the carpet. A lick of the hand. The way, for a long time, he sucked small rocks, but knew he wasn’t supposed to, so he’d reflexively spit them out when he saw one of us coming.

The day before the last day, I went to the park with Harvey and there was another little boy using a woodchip as a key, turning and turning it in the air and saying, “It opens the door.” And well. Someone had to open it.

A bird leapt upward and did that thing birds do, where it folded its wings but kept ascending, jumping up and up on only gusts of wind.

I saw dogs playing in a field over the hill, so far away I couldn’t hear any sound. They jumped and ran in the sun, and were so active but so distant from me that they were a vision of the afterlife, a glimpse of the Heaven where I knew Paul would soon go. He is there now, and I’m there too, because there is no time in Heaven. All time is the same time, so we are already together, there will never be a minute when we are apart.

Paul, oh I loved you. Oh I love you, forever. You were, you are, a very good boy. The best. The true hero of my heart, one of the true loves of my life, a part of my very being and soul. So sweet. So kind. So perfect. So very, very dear.

Paul and Adrienne, together forever.