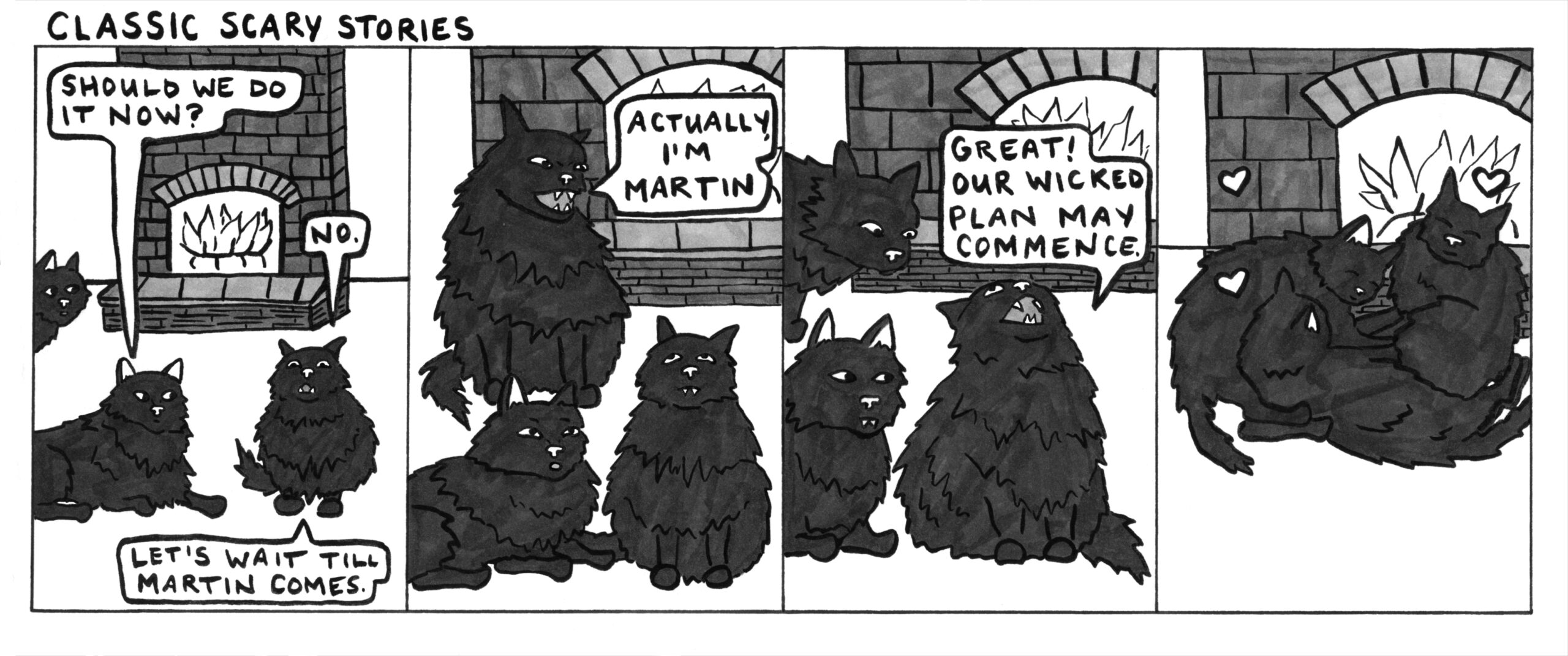

Does everyone remember this particular Scary Story To Tell in the Dark? It’s called “Wait till Martin Comes,” and I remember listening to it on car trips as a kid—a memory somewhat smeared together with watching the Twilight Zone episode “The Howling Man,” because both stories involve a man on a walking tour, lost in a storm. The concept always felt so fearful and foreign to me: walking somewhere with no car to return to, no train to catch at the very last stop. Just your knapsack and a pair of good shoes, and the kindness of strangers—or not, depending on what kind of story you’re in.

Anyway, Dave and I are going on a walking tour in France this fall, and I hope we encounter neither large carnivorous cats nor the actual devil.

This past weekend, we took a road trip to the small southern Arizona town of Bisbee, because, as Dave puts it, once a year I get the urge to see what it would be like to travel with our dog. It’s always a mixed bag, to be honest! Of course Paul is a delight to be around, and we think he’s happy to be with us, but he gets extreme car anxiety, and moderate strange-place-who-are-these-people anxiety, which can make it a little hard to know how much we can do with him.

We stayed just outside Bisbee proper, in a yurt at the top of a small mountain. I had never been in a yurt before, so I can’t say how this one stacks up, but it was lovely, like being inside and outside all at once. Within, a bed, a kitchen, a couch, a small wood-burning stove, and a coffee pot; without, a porch that looked out over a rolling green expanse, and offered a magnificent view of the stars. It was windy, and so at night large gusts would whip through the mesh windows, shaking the structure and making us feel more than once that we might be blown away. I don’t know why this was such a pleasant feeling, but it was: something Mary-Poppins-like, as if we were living inside her umbrella; something of Robinson Crusoe and Peter Pan.

The town of Bisbee is set into the hillside, each house unique in shape and structure to accommodate its unique parcel of land. Some were crowded together like teeth, some were surrounded by ruins—Bisbee was once a thriving mine town, then it was a ghost town, and now it’s the domain of artists and burnouts and hippies and tourists like me, with their dogs. (They really loved dogs there; any time the question was, “Can we really bring our medium-sized dog into your store full of antique glassware on low shelves?” the answer was, perplexingly, yes.) We made a game of trying to guess which buildings were abandoned and which just decrepit, but we couldn’t always tell: some of the most blown-out places were full of art, or had curtains in the windows of an upper floor. It is a town that holds its mystery close.

There are also stairways everywhere in Bisbee: they call this the “Bisbee 1000,” meaning, I suppose that you can walk up 1000 steps if that’s your thing. (We didn’t do the full number, but we did enough that my calves are still sore three days later. It’s great. My crumbling human body is great.) It’s such a small town, you could walk through most or all of it in a single day, and I got a strong feeling of what it would be like to live there as a teenager: trapped and desperate to leave, but also protected by the hills, protected by your secret knowledge of shortcuts and vistas, gathering places that transform in the dark and always feel safe. Smoking beneath a streetlamp. Laughing in the shadows. You could go anywhere on foot, or on a bike, and it would feel like you were cut off from the world, and also like you owned it.

I could imagine being a child there, even though I’ll never be a child again. Isn’t that funny? We’ll none of us ever be children again. We will always be this, our bodies marching towards the end, towards whatever’s next, but there are moments when I remember what it was like, and in those moments no time has passed, and there is no difference. I am walking out my mother’s front door at ten p.m. to go to the beach, sneaking down the old wood steps into the sand, into the dark.