I’ve been thinking a lot about clothing as costume. The genesis of this thinking lies in the podcast I’ve been listening to—the same podcast lots of people I know online have been listening to, about the novelist Donna Tartt and her friends when they were undergrads at Bennington College.

In a lot of ways, I’m not sure I really like this podcast—I mean, I like it, I’m obviously listening to it, but the appeal is prurient; I’m not sure it should really exist. Donna Tartt is famously private, and has openly objected to (indeed, litigated about) the fact that the show makes use of letters she wrote to her friends at age 18. I would object too, probably, even though it’s undeniably interesting to see (hear, feel, sense) the journalist poking around behind the scenes, connecting real-life people and events to those in Tartt’s famous first novel, The Secret History. You could argue, I guess, that if Donna Tartt borrowed so much from her own life to make art, that it shouldn’t be out of bounds for the journalist to borrow the same material for inquiry and criticism.

But the one is not the same as the other, is it? Art is transformative, whereas journalism is revelatory, and I’m not really sure that what’s being revealed here needs to be, at least not over the objections of its subject. And yet…I’m still listening to the podcast.

Back to my actual point: in this podcast that I feel bad about liking, there is a lot of talk about the students’ aesthetics, how some of them cloak themselves in preppiness or sunglasses or hippie chic, and some affect the look of Oxford schoolboys in the early 1900s. There is a specific distinction drawn between those students who arrived at Bennington with their look in place, and those (like Donna Tartt) who consciously changed it—and changed, along with their looks, their whole life. This is the purview of college, of course: building oneself anew, building oneself from the ground up, discovering the mutability of identity and the power of choice. It can be the purview of any time in one’s life, theoretically, but that’s a particularly potent one. I remember going to college and becoming a hipster, tilting my thrift shopping onto a new axis. I’ve changed my style a few times since then, but have I ever changed it so consciously? With a goal in mind? I do periodically try to be the kind of person who wears blazers, but it’s difficult in Arizona; it’s so hot here. Blazers make no sense most of the year. Perhaps this is a failure of will.

I do wonder, though, what costume I am actually putting on, what my subconscious thinks it’s projecting when I choose my clothes. At the moment, I’m wearing a turquoise jumpsuit and sneakers, a slightly affected look for the home, except when one considers that the whole ensemble is basically pajamas. I have a lot of turtlenecks and high waisted jeans for fall; in the summer I pretty much only wear loose cotton t-shirts tucked into shorts, but as I said, Arizona heat makes it difficult to project anything but sweaty discomfort. During the pandemic, all my nail polish moldered in a drawer, where it is moldering still. Do I want to paint my nails? And if so, to what end, when the body will ultimately die and return to dust? This is a real question that I ponder, and also very much the equivalent of a Calvin & Hobbes comic when Calvin refuses to take a bath on the grounds that he’ll only get dirty again.

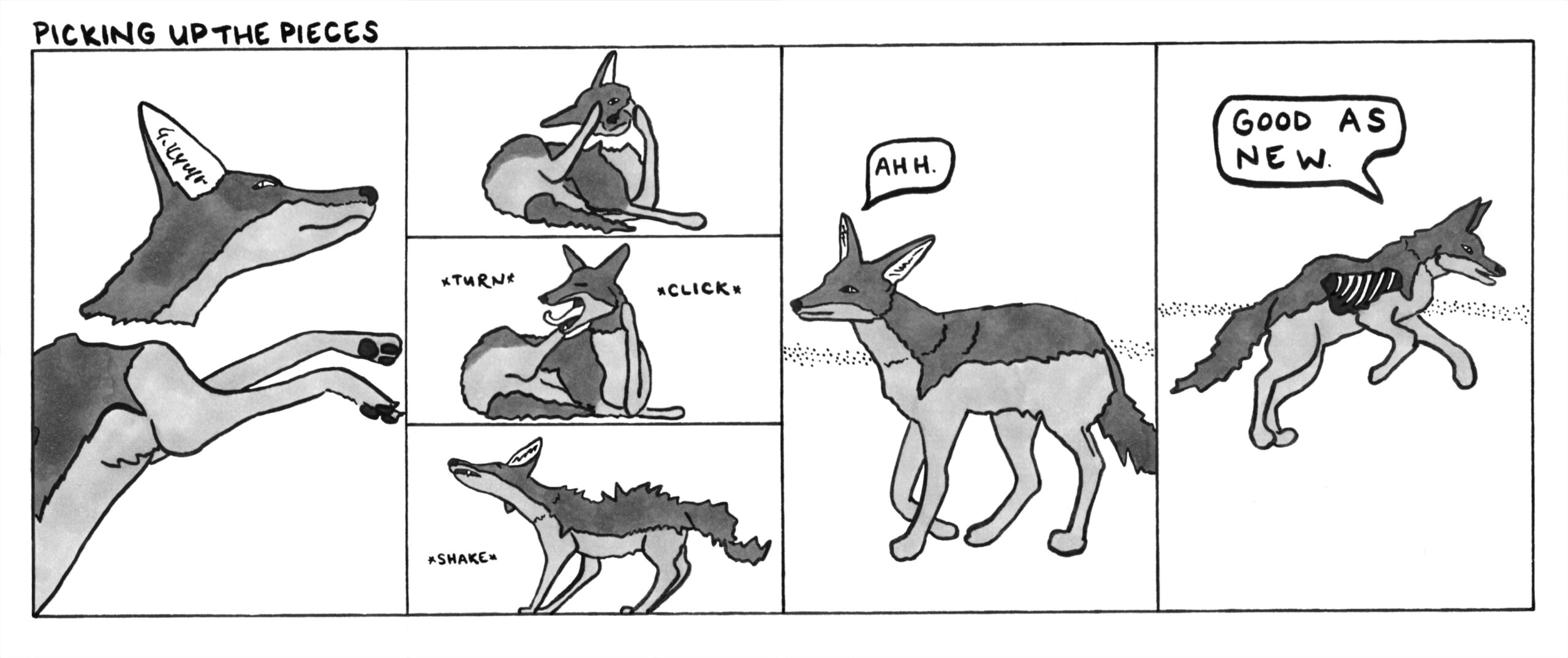

Our aesthetics, like our senses of self, break down and have to be put back together. It is the change of the season, the season of costumes and spook, and so an appropriate time in a way to think about clothing in terms of death and rebirth. I’ve had the same Halloween costume for the past eight years or so: a red crayon, which always draws compliments from children.

The real announcement, of course, it that it’s cool enough outside to wear a jumpsuit with long sleeves; by tomorrow it’ll be back in the mid-eighties, but today it’s downright chilly in the shade. Talking about the weather is of course just my way of weaseling out of making a larger point, drawing a truly satisfying conclusion about how we dress to create the person that we think we are; how our exteriors and interiors are more closely aligned than we want to believe; how one of my composition students once became incredibly despondent when I pointed out that a casual aesthetic is as much a choice and a sales pitch as something fussier or more high-tone. (This was for an essay he was writing; I wasn’t just being weirdly critical.) (Though it’s kind of relevant, because he was a college freshman, same as Donna Tartt the year she started wearing well-cut suits.) (We all make our choices, is what I’m saying, and believe them to be right. Whereas rightness does not as such exist. But you are, I think, allowed to have fun.)